bait balls

gaggles of geese

algae and fungus

lichen and granite

algae and coral

coral and parrot fish

moose and wolves

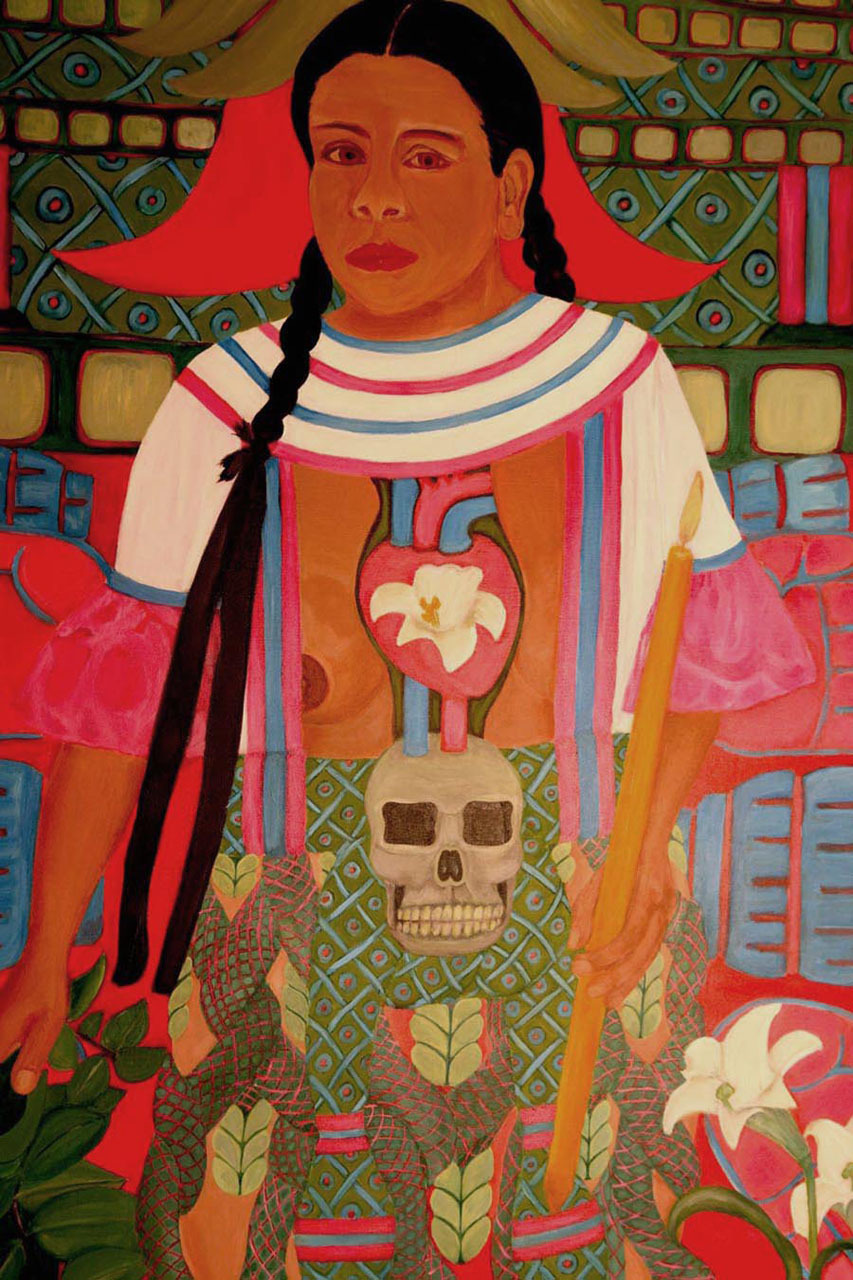

mother and child

aster and goldenrod

When you stop and think about it, everything in this world is in a relationship of reciprocity.

The school of horse eye jack swim in concert, the individual safer en masse, cooperating to avoid the hungry sword fish. The geese fly farther in formation as they rotate from point to flank of the flying wedge. Algae and fungus live in such reciprocity, that we think of the two as one: lichen. One giving food, and the other returning habitat. Together, they break down rock, which eventually contributes to the dirt that feeds the plants that feed the animals that feed us.

Parrot fish poop beautiful white sand, which we love under our toes in Florida, but they also eat the over growth of algae on corals when that plant runs amok to nearly strangle its friend the coral polyp-- still more reciprocity. Mother nurses child. And what does child give? The child offers its helplessness and dependence and the pleasure of this bond elicits the production of oxytocin in the brains of both mother and babe, bonding them even more surely one to another. The child grows up safely to advance her species and one day have her own baby perhaps. In contemporary, social reciprocity, we parents hope our children will grow up to be the stewards of ourselves and the future too.

Reciprocity is everywhere, as we learn from naturalists like Katy Konrad, when they connect us to the web of life (what we called "the food chain" in my own youth). The wolf and the moose highlight essential reciprocity. In the right balance, wolf picks off weak or diseased moose, keeping genetics in check. The wolf eats and its own genetic line is tested by the challenge of bringing down the giant. We are not plants, producing our own food from sunlight, we must consume, of course. We do not necessarily equate such elemental reciprocity with social and emotional skill or growth. But consider the aster and the goldenrod.

Botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer asked a question when she applied to forestry school as an 18-year-old undergrad: Why are the aster and the goldenrod so beautiful together? The university accepted Robin, but they suggested that she should take her question to the art department. Robin entered the forestry program, despite feeling embarrassed by the initial reaction of the scientific community there. Good thing she stuck with botany. As it turns out, goldenrod and aster are more beautiful together for a very good reason. Together, their blooms striking vibrant notes on opposite ends of the color spectrum, they attract more pollinators by virtue of the attractive composition they create. The beauty of reciprocity is external, and intrinsic.

Today, I visited a Camp Fire club at an affordable housing community in Saint Louis Park. I watched as the kids ran and played together. One child fell and scraped her knee. An adult facilitator came to her aid, kneeling by her side, speaking to her quietly and calmly. Next, a peer approached and knelt too. She looked into the face of her crying friend, making eye contact, asking questions. Both children leaned against the adult, and the friends hugged, the elder peer planting an absent kiss on the head of her crying friend. These three people together formed a scaffolding of social and emotional learning. Communication and empathy in action. The children learning care and comfort from the action of the adult. The older child easily practicing a gesture of comfort that had likely been extended to her and learned from parents again and again; she grows her own confidence through the capable care of her younger friend. The younger child learns resilience and grit through that care. With some help, the girl gets up and the game goes on, trust following in its wake-- each brain and heart physically better off for the acts of compassion given and received. So simple, but so wonderfully complicated and related.

Like the aster and the goldenrod, we are more beautiful, and healthier together. As Vygotsky pointed out long ago, children learn and grow better together. Social scaffolding affords us the practice for effective interaction, insurance for a more peaceful and productive society.

So humans, like the rest of the natural world, practice reciprocity. And we also reciprocate with the natural world. Consider our relationship to food. Here is the opportunity to practice true reciprocity. We give the earth adequate care and it gives us healthy food to eat. Trees? They take up our carbon dioxide and give us oxygen, food, medicine, shelter and fuel (perhaps this relationship is a bit lopsided). It is natural and beneficial to practice reciprocity with each other, and the earth we share. Just one more reason that nature is the best catalyst for human development.